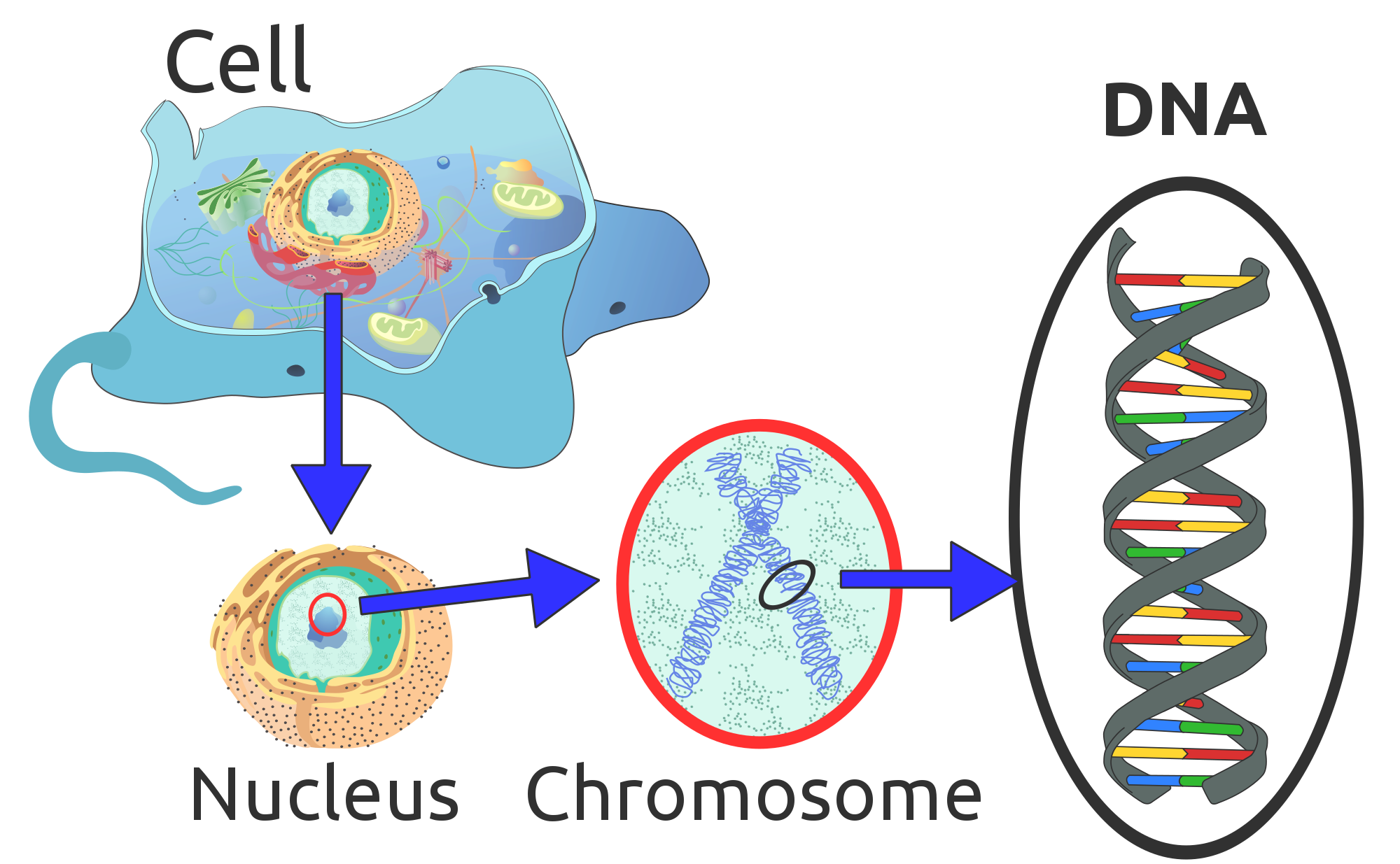

In response to an invitation I addressed the latest meeting of the New Zealand Law Society (Wellington Branch) held at the Law Society building in Wellington, New Zealand, on the 18th of June 2015. My brief was to try and shed greater light on DNA evidence, an evidence type that members often find confusing. The confusion, I suggest, arises from the terminology and vocabulary used which, in many cases, offers little clue as to meaning. DNA evidence is in fact a combination of chemistry, biology (and a number of sub- branches) and statistics. The same term can have different meanings depending on the science, e.g. to a chemist ‘sensitivity’ is the gradient of a response curve (the size of the signal for a given change in parameter measured) and to a biologist the limit of detection/quantitation (how little can be detected). If scientists can be confused what hope for lawyers?

SWGDAM offers a helpful glossary but even then confusions remain, e.g. what is and what is not a random or stochastic effect?

Interpretation of complex mixtures (more than two contributors)

After an introduction to the chemistry, biology and statistics behind the evidence type the discussion broadened to current issues. These issues stem from the ability of the latest profiling products to obtain a DNA profile from just a few cells. The results are very often mixed or complex profiles where there

After an introduction to the chemistry, biology and statistics behind the evidence type the discussion broadened to current issues. These issues stem from the ability of the latest profiling products to obtain a DNA profile from just a few cells. The results are very often mixed or complex profiles where there is evidence of more than two contributors. How to interpret these complex profiles has been the subject of much debate over recent years and I think it is fair to say that consensus has yet to emerge.

Different labs use different approaches, making different assumptions which obviously yield different results. It could be argued that until consensus is reached the interpretation of complex mixtures should be restricted to use as an investigative tool rather than be adduced as evidence. If science is undecided then what help can it be to the trier-of-fact?

Secondary transfer and Contamination

Other consequences of technological advances are that contamination and secondary transfer become more problematic. One of the fundamentals that assure the forensic utility of DNA evidence is the fact that human beings shed cellular material. Given the large numbers of cells shed, an individual’s cells will transfer by whatever means are available. The finding of an individual’s cellular material at a crime scene may not be evidence of presence. Innocent individuals might find themselves the subject of police enquiries, a situation that should be of concern to citizens and legislators.

Anti-contamination procedures become increasingly complex, burdensome and expensive. As complexity increases so does the risk of failure and error.

Interpretation and software packages STRmix™

The discussion then turned to more parochial matters. The New Zealand forensic science provider ESR is using ,and commercially marketing, a complex mixture interpreter: STRmixTM. Given that ESR, with its Australian partner, are looking to sell this software package overseas it seems likely that intellectual property issues may be used as an excuse to close the product off from independent scrutiny (so called ‘black boxing’). However, the recent admission by the FBI of errors in its DNA evidence going back to 1999 provides compelling support for the argument that the validation data and all relevant studies for DNA interpretation software must be open to independent scrutiny.

Laboratory Error

A step in the interpretation of DNA evidence is the calculation or estimation of a random match probability – the chance of a false positive. Given a full profile and one major contributor this is often an unimaginably large figure. Advances in technology, specifically the addition of extra loci (CODIS 20 and DNA 17), have the potential to significantly increase this number such that the likelihood of laboratory error may have to be taken into account when interpreting DNA evidence.

Investigative v Evidential value

Perversely, technological advances have the potential to reduce the probative value of DNA evidence. Advances certainly improve its utility as an investigative tool but the complexity of the interpretation can put the evidence beyond the understanding of the average juror.